Why do we fall for April Fool’s jokes?

For humans, relationships are rewarding and help to fulfill a basic social need to belong. And one of the key ingredients required for a successful relationship is trust. Unsurprisingly, research indicates that we are more likely to trust someone in our close social network.(1) In fact, a 2017 study of twins suggests that while our approach to trust may be influenced by our genes, distrust is linked to nurture, not nature.(2) In our last Everyday Science with Dimensions post, we zoomed in on the science behind the “love hormone” oxytocin. Not only does it bring out our warm and cuddly side, it is also responsible for a substantial increase in trust levels:(3) although, the good news is, it doesn’t seem to make us more gullible.(4) So it seems we instinctively want to believe information from those in our trusted circles.

When trust turns bad…

Not all of us are predisposed to accept what we are told at face value though – even when it’s a loved one whispering it in our ear. And that can be helpful; along with objectivity, creativity and curiosity, a questioning mind is a valuable characteristic for many career paths, including research.

But, for some of us, that desire to question can tip over into a fear of being duped or exploited, also known as sugrophobia. Some researchers argue that this kind of paranoia is the inevitable cost of the suspicious mind we have needed to survive as a species.(5) For some groups, it can lead to a belief that things many of us accept as fact, are, in reality, hoaxes. This has led to the emergence of flat earth campaigners, climate change deniers and groups that claim man never landed on the moon.(6) Some researchers suggest that belief in these, and other conspiracy theories may be driven by a desire to be unique and stand out from the crowd.(7)

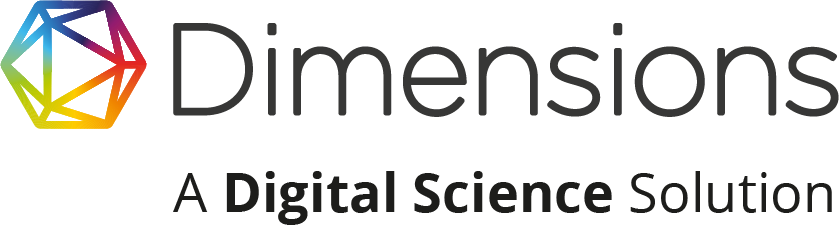

In an ironic twist of fate, at least one hoax has gone on to become a genuine research topic. Back in 2014, several outlets repeated a story from a satirical website that the American Psychiatric Association had designated “selfitis” (the compulsive desire to take photos of yourself to post on social media) a new psychiatric condition. While it was meant as a joke, researchers saw the possibilities and the 2018 article An Exploratory Study of “Selfitis” and the Development of the Selfitis Behavior Scale now has an Altmetric score of 1,609.(8)

Figure 1: A screenshot of the article “An Exploratory Study of “Selfitis” and the Development of the Selfitis Behavior Scale” in Dimensions.

The science of laughter

One of the biggest reasons we carry out hoaxes is to provoke laughter. And studies have shown that a good chuckle or giggle can have beneficial effects in situations as diverse as pain management,(9) palliative care,(10) and, crucially, working in a research lab!(11) And it can help with conditions such as stress and depression,(12) emotionally-induced over-eating,(13) and Parkinson’s Disease.(14) It can even encourage us to exercise more as we grow older.(15)

Here are a few facts we gleaned from the free version of Dimensions by running a topical search for laughter (NOTE: all data for this article were extracted from Dimensions on 03.22.19).

Researchers

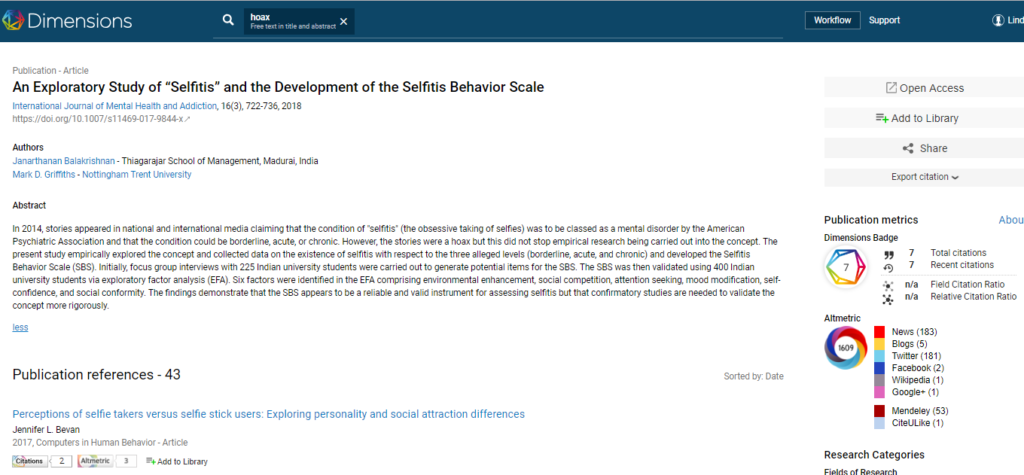

The auto-generated analytical views tab reveals that the most published researcher on the topic is psychologist Willibald Friedrich Ruch of the University of Zurich in Switzerland. 36 of his 225 publications listed in Dimensions focus on laughter. Papers include A lifetime of fear of being laughed at and Neural correlates of laughter and humor, which has been cited 199 times to date.

Figure 2: Papers on the topic of laughter published by Willibald Friedrich Ruch.

In Dimensions, publications are linked to other content types to provide a full view of the research landscape and easy exploration of the connections between relevant grants, clinical trials, patents and policy documents. A look at Professor Ruch’s profile page shows he has also been awarded three grants for research into the topic, including nearly 200,000 euros from the Swiss National Science Foundation for The joyful face may hide an evil mind: Individual differences in fearing laughter – an investigation into the social and emotional context of laughter styles.

Interestingly, if we look at the locations of the 20 most published authors on the topic, the UK and Belgium feature prominently and only three are based outside Europe (in the US).

Publications

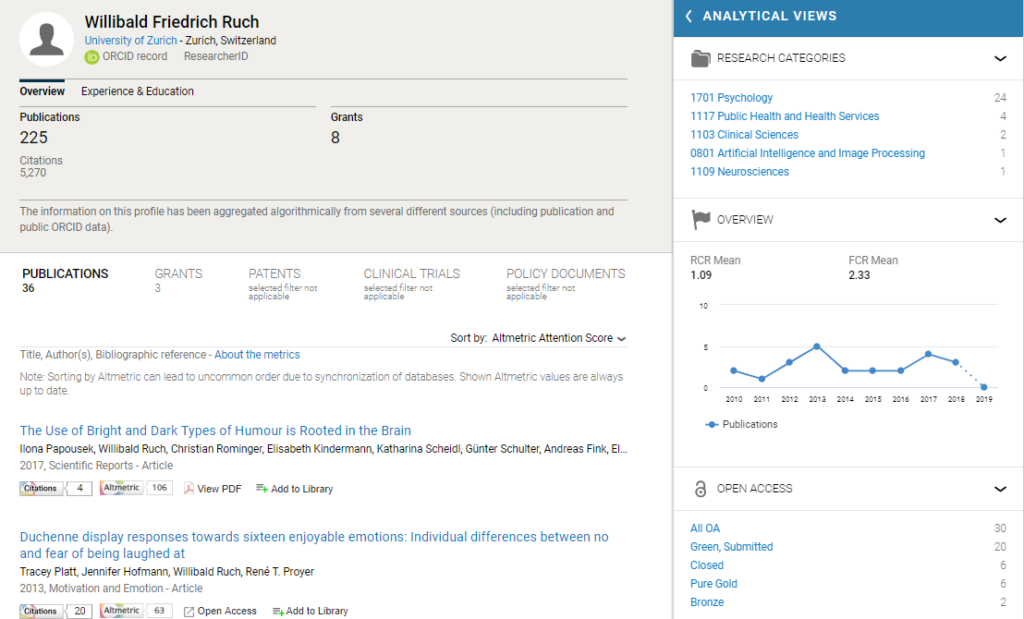

The Dimensions publications linked to laughter stretch right back to 1645, when “Teares, and Laughter: The Complete Poetry of Robert Herrick, Vol. 1” was published. Since then, there have been 5,563 publications – sort these by citations and we can see that Stanley Milgram’s 1963 Journal of Abnormal Psychology article, “Behavioral Study of Obedience”, has received the highest number of citations to date (1,900). It studied the use of electric shocks as punishment and found that one of the outcomes (along with sweating, trembling, and stuttering) was to make the participant laugh.

Figure 3: A screenshot of the article “Behavioral Study of Obedience” in Dimensions.

Figure 3: A screenshot of the article “Behavioral Study of Obedience” in Dimensions.

In contrast, the article which received most online attention (as measured by Altmetrics) was the 2017 Current Biology publication “Positive emotional contagion in a New Zealand parrot” by Schwing et al, with an Altmetric score of 916.

Publications by year

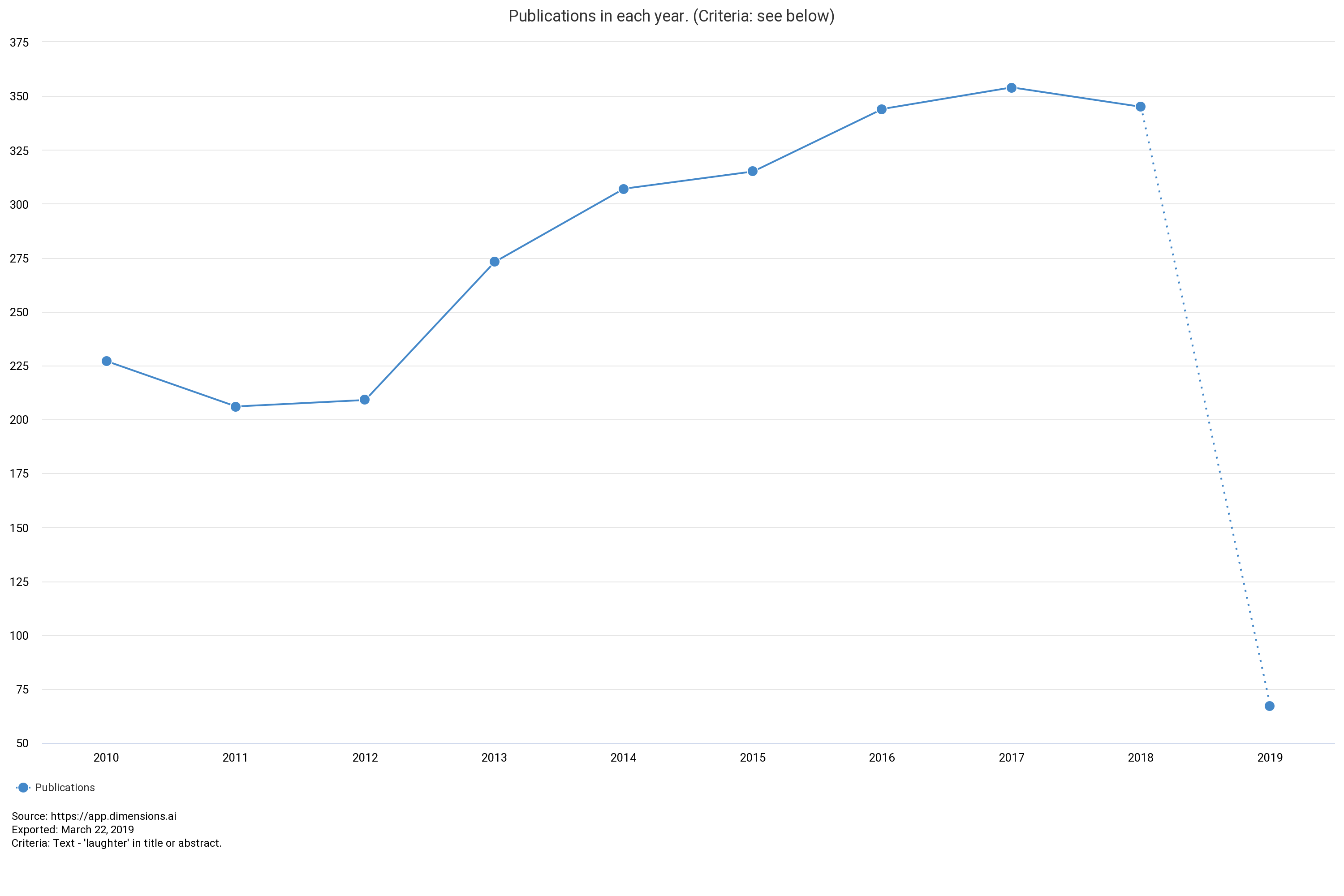

Publications related to laughter have been rising steadily in number over the past eight years – increasing from 227 in 2010 to 345 in 2018.

Figure 4: The number of laughter-related publications by year (2010-2019) in Dimensions.

Figure 4: The number of laughter-related publications by year (2010-2019) in Dimensions.

Grants by year

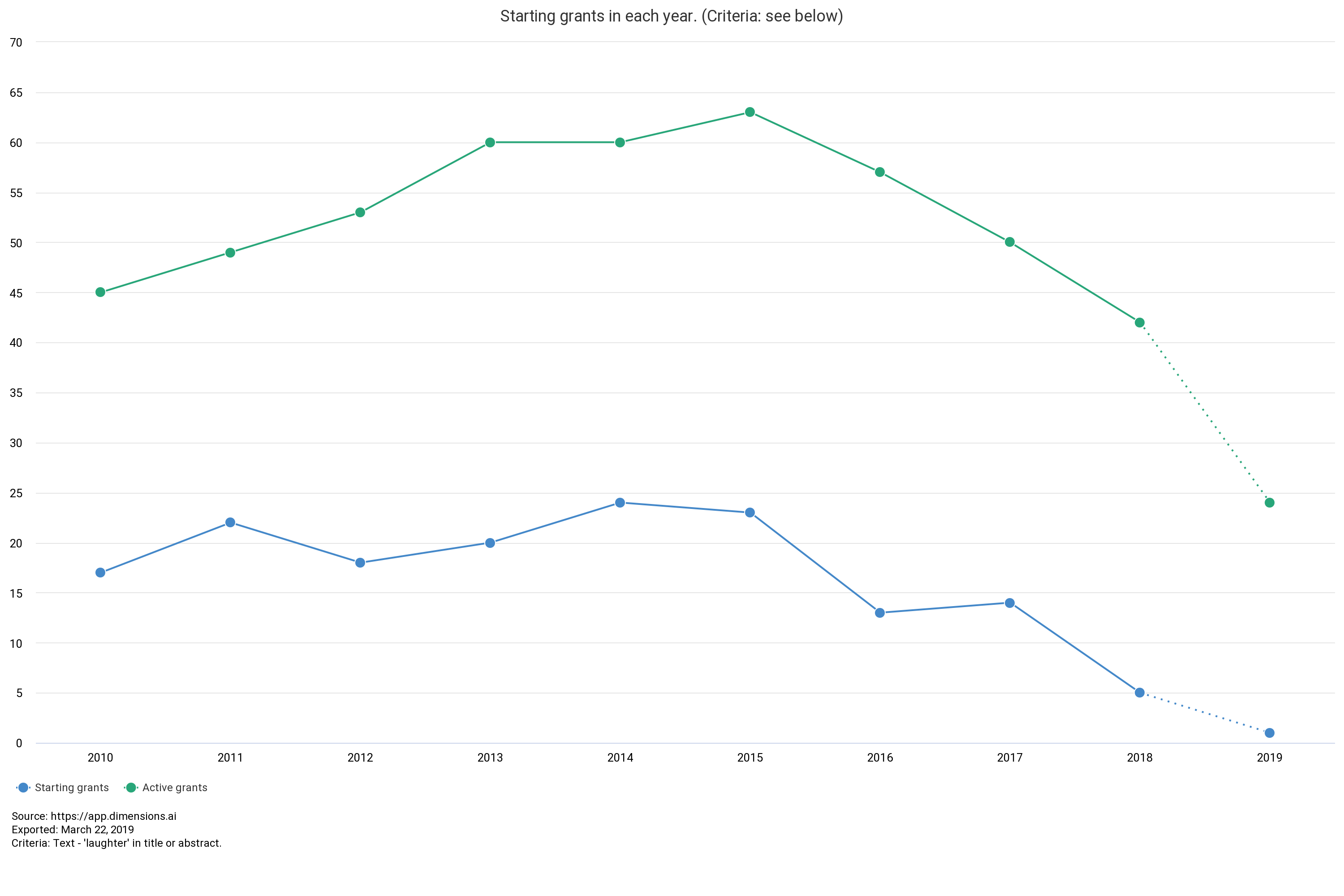

Figure 5: The number of laughter-related grants by year (2010-2019) in Dimensions.

Figure 5: The number of laughter-related grants by year (2010-2019) in Dimensions.

While publications may have peaked in 2018, as we can see in figure 5, active grant funding hit its highest point in 2015 – possibly an indication that we can expect the upward trend in laughter-related publications to continue in the short term. However, with the number of starting grants falling from a peak of 24 in 2014 to five in 2018, longer term, we are likely to see a drop in publication numbers.

The scope of those grants has varied enormously, ranging from the relationship of laughter to the Zen Buddhist religion and the experiences of care workers participating in laughter therapy, to the effects of immigrants and ethnicity on American humor. One of the biggest sums awarded was 2.8 million euros by the European Commission. It was given to a group of universities to help computers and machines that interact with humans learn to deal with laughter.

The top five funders to date are:

- European Commission (EC) (Belgium) EUR 22.8 M

- Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) (Japan) EUR 5.8 M

- John Templeton Foundation (Templeton) (US) EUR 5.0 M

- National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) (US) EUR 4.0 M

- The Research Council of Norway (RCN) (Norway) EUR 2.0 M

Patents

81 laughter-related patents have been granted since 1979. The top five recipients vary widely in location and sector. Mitre, a not-for-profit company in the US tackling problems that challenge the nation’s safety, stability and well-being, filed the most (four). All focus on audio hot spotting (detecting non-lexical audio cues, such as laughter). Nice Systems, an Israeli organization providing solutions for intelligence agencies and law-enforcement organizations, etc., also filed four patents, all centering on a method and system for laughter detection.

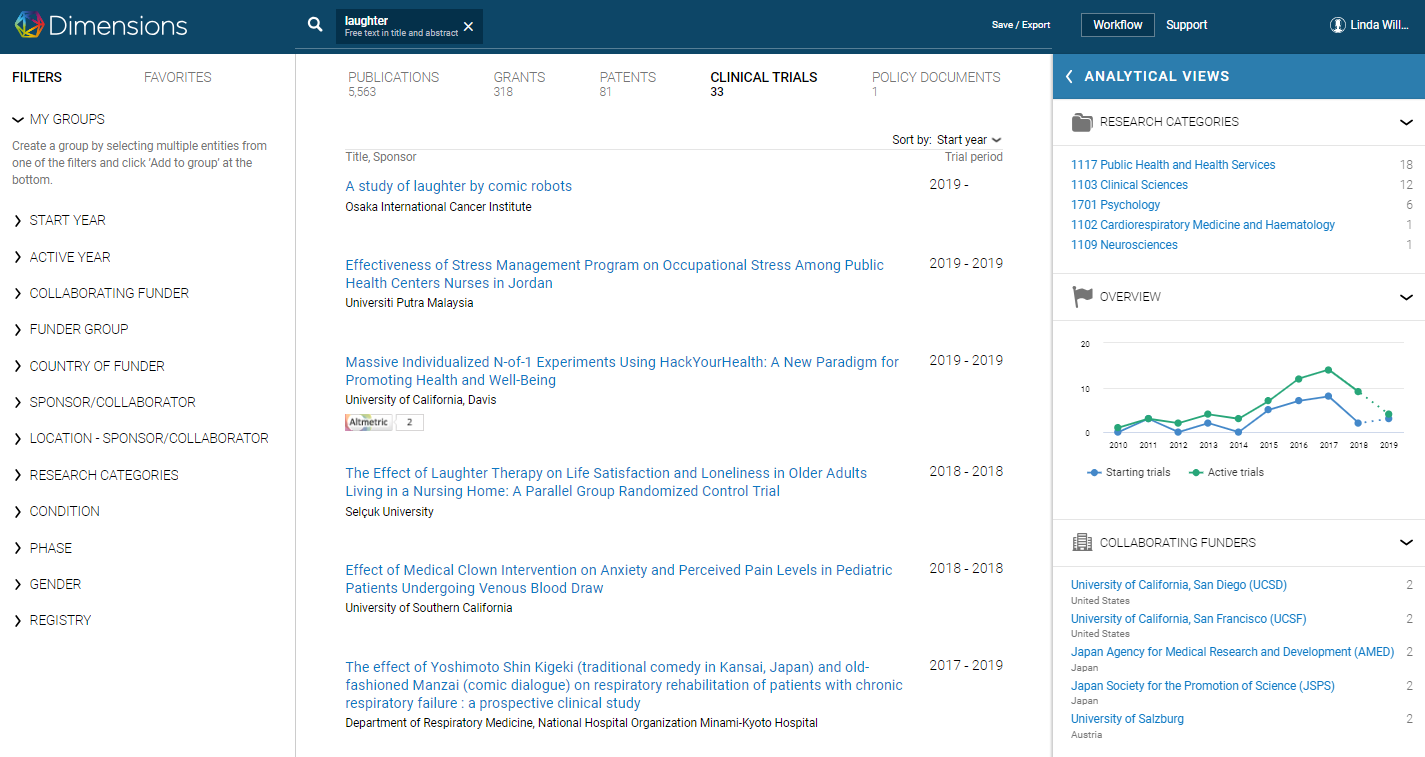

Clinical trials

As we’ve seen in this article, there are many medical benefits associated with laughter, and there are 33 related clinical trials in Dimensions. The most recent of these is being run by the Osaka International Cancer Institute in Japan, and looks at whether comic robots can entertain oncology patients. Others look at the role of laughter in helping elderly people with loneliness, nurses with occupational stress, and pediatric patients with pain.

Figure 6: Some of the laughter-related clinical trials recorded in Dimensions.

Figure 6: Some of the laughter-related clinical trials recorded in Dimensions.

April Fool’s Day: the science behind the laughter

We’ve seen that laughter is one of the benefits of practical jokes and those benefits are extremely wide-ranging, attracting the interest of researchers – and organizations – around the globe, in fields as diverse as AI (artificial intelligence), health, and national security.

But there are other plus points too. For example, anthropologists believe that the initiation-style pranks people undergo when entering a new social group, can help to create a sense of belonging.

For some, practical jokes can provide a safe outlet; a way for us to experience fear, shock or concern in a non-threatening environment. They can also increase self-awareness, helping us work out how we could have responded differently and making us question why we were duped in the first place.(16) For children, in particular, they can be a useful way to learn the difference between lies and truth.

Dimensions’ wide range of content allows you to gain new insights into your chosen topic. Feel free to reach out to the Dimensions team to learn more about the content scope and coverage and see how Dimensions can help you find the most relevant results faster.

References

1 Computational Substrates of Social Value in Interpersonal Collaboration

2 Trust is heritable, whereas distrust is not

3 Oxytocin increases trust in humans

4 Oxytocin Makes People Trusting, Not Gullible

5 Social threat perception and the evolution of paranoia

6 NASA Faked the Moon Landing—Therefore, (Climate) Science Is a Hoax

7 Too special to be duped: Need for uniqueness motivates conspiracy beliefs

8 An Exploratory Study of “Selfitis” and the Development of the Selfitis Behavior Scale

9 Social laughter is correlated with an elevated pain threshold

10 The Use of Humor in Palliative Care: A Systematic Literature Review

11 Why laughter in the lab can help your science

12 Therapeutic Benefits of Laughter in Mental Health: A Theoretical Review

13 Laugh Away the Fat? Therapeutic Humor in the Control of Stress-induced Emotional Eating

15 Evaluation of a Laughter-based Exercise Program on Health and Self-efficacy for Exercise

16 Feeling duped: Emotional, motivational, and cognitive aspects of being exploited by others.