“Working with a database as comprehensive as Dimensions to create a scientifically justified and transparent metric.”

Janne Seppänen, Open Science Centre, University of Jyväskylä

The challenge: Journal prestige and how bias has damaged research

For a long time, scientific research has been guided by journal publication. But ‘journal prestige’, as Janne Seppänen calls it, means good, accurate science is missing the attention it deserves.

“We’ve maintained a system that selects bad science because we reward each other for getting into high prestige journals. Many scientists acknowledge this is a problem, but there’s no consensus on how to address it. I would like science to be fair and as good as possible.”

Despite the fact that prestigious science journals struggle to reach even average reliability, and are often considered ‘elite, exclusive and exclusionary’, an unconscious bias exists, favouring the research they feature, and the academics behind that research. This skews the research that gets read, biases hiring and headhunting processes and in some cases, results in scientists leaving the field, when their potentially ground-breaking work becomes effectively invisible to the community.

Janne Seppänen at the Open Science Centre, University of Jyväskylä, Finland, wanted to find a new way to evaluate the influence of a piece of research – one that allowed everyone to discover good, accurate science, regardless of who wrote it and where it was published.

The need for new metrics

Janne is not alone. 21,829 individuals and organisations in 158 countries have now signed DORA, a Declaration On Research Assessment, pledging to improve how the output of scientific research is evaluated.

At one time the preferred method was the Relative Citation Ratio (RCR). Developed in 2016, its algorithm uses citation rates to measure influence at the article level, comparing the number of citations a target paper receives to a comparison group formed by papers that are cited alongside that target paper.

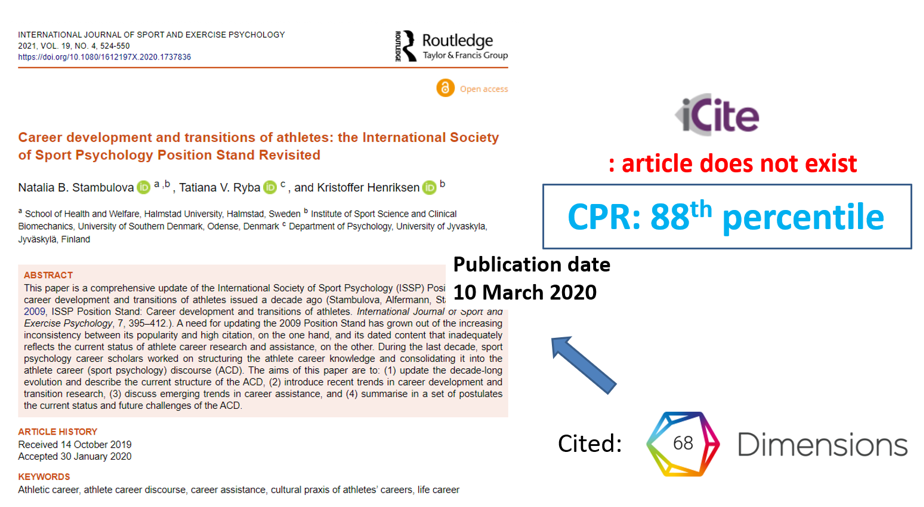

For Janne, the foundational idea of RCR was great, but the implementation was poorly executed in many ways. First, distributions of citation rates are highly skewed – only a small number of papers get cited extremely often and thus have a disproportionate impact on the mean – yet RCR compared the article’s citation rate to the arithmetic mean of the comparison group. Worse, RCR did not even use the actual article-level citation counts, but used average citation rates of journals represented in the comparison group. Citation rates were calculated in terms of citations per calendar year, combining papers published in January with papers published in December. Finally, the implementation available at iCite was based on citation data available in PubMed only.

Janne says: “In most fields of research, PubMed, which is used as the source data for RCR in its available implementations, is very sparse. So it doesn’t index most of the publications. And even if it indexes your target publication, it certainly doesn’t index all of those that cite it, which means that it’s missing a lot of data… I wanted to build a new metric that used this basic idea but had the true article level citation data as inclusive as possible, and calculated the rates on the best available resolution rather than in terms of citations per calendar year . Working with a database as comprehensive as Dimensions, I could see how many times a piece had been cited per day since it appeared and then calculate percentile rank by comparing it to a fair peer group.”

To find good, relevant sources the algorithm needed a far greater data set and metrics that covered more than just citations.

“Some people think the answer is to do away with metrics altogether, simply letting research speak for itself. But there just isn’t enough time to read everything out there even if you are an expert, so scientists need some direction in what to pay attention to. And there are lots of non-experts – science journalists, policy-makers, teachers, for example – who also need some way to judge what science to pay attention to.

We need more metrics, but they need to be better, more diverse metrics. Scientifically justified and collected using transparent methods that show academic impact, but also societal impact and educational impact and so on.”

This thought process led to a new collaboration with Dimensions.

Bringing missing data to life

Using the powerful API and search language from Dimensions, Janne developed the Co-Citation Percentile Rank (CPR), which uses Dimensions extensive database, the largest of its kind in the world, to compare the citation rate of any article that has a DOI and is indexed, to the actual citation rates of articles that are co-cited along with that article.

From here, the CPR system analyses the comparative set of peer articles and reveals a percentile ranking which is fair as well as comprehensive. In Janne’s words this “makes intuitive sense and allows for a truly journal-independent research field – normalisation for quantitative comparison of academic impact.”

For users, the results are exciting. Not only can they find data previously missed, they can understand its importance quickly.

Science for everyone

For Janne, the creation of a fairer, more equal landscape for scientific research went hand in hand with a publicly accessible platform that would allow everyone to benefit.

“I wanted people to be able to use CPR freely, and we also published an explanation of the metric. The source code is openly available so other universities and funders could build their own versions too.”

Dimensions agreed. Working collaboratively they created JYUcite, a publicly available demonstration that supports fairer evaluation of scientific research.

Janne says: “The team at Dimensions has always been eager to help. You get the feeling that they want academics to use their data to build things and they want to make it possible.”

Going forward there is scope to use CPR within universities, for research funding decisions, recruitment, for science journalists, or really anyone seeking to find focus in the large body of relevant scientific literature in any topic.

Find out what Dimensions can do for you

Would you like to learn about how Dimensions can support research within your organisation? Get in touch and one of our experts will be happy to speak to you.